Roosevelt Pires

Master of Handmade Violins and Bows

South End String Instrument. A Rich Cultural Legacy of Musical Craftmanship from the Cape Verdean Islands: South End String Instrument

Roosevelt Pires, born on the Cape Verde Islands, and one of the best-known string instrument builders in the United States, stands in his small studio at South End’s Boston Center for the Arts on Tremont Street where he holds a 1790s Portuguese violin in his hands. A customer recently traveled to Boston from Portugal to have Roosevelt repair it. “I am going to make it sing again,” he says. “It needs to be French-polished.”

In the crowded BCA shop of South End String Instrument, where Roosevelt has spent his days since 1999, rows of violins hang from the walls, between thick tails of long black and white strands of horsehair. He says he prefers tail hair of Mongolian stallions for the rehairing of his bows, which allows for the seasonal shrinkage and expansion the New England climate requires. Another shop corner is stacked three cases-deep with a multitude of different-sized string instruments, waiting for repairs. “The kids from the Boston Community Music Center,” he explains; Covid closed their music program in 2019, so he still has time before the instruments are needed.

Roosevelt was brought to Boston in 1979 as a teenager from the Cape Verdean Island of Brava, off the west coast of Africa, by his father, Ivo Pires, who had emigrated to Boston in 1967. The father had an established reputation as a self-taught string instrument maker and violinist who had built his first mandolin when he was nine, using cedar shingles from his mother’s house. Roosevelt was being raised by Ivo’s mother on Brava while his father was working as an instrument maker for various companies in Boston.

When Roosevelt arrived here, his father enrolled him at Cathedral High School in the South End; Roosevelt spoke only Portuguese and Creole. The nuns would translate sentences from English into Spanish; it was close enough to Portuguese, so he could figure out what the likely meaning was. After the school day ended, “Rosie,” as his father called him affectionately, would run to Ivo’s violin workshop where he learned everything about string instruments from the master craftsman himself.

At age fifteen, Roosevelt worked on the bow of YoYo Ma. A photograph of the young Roosevelt holding the world-famous cellist’s bow, is mounted on the South End String Instrument’s wall, next to a signed one of YoYo Ma himself.

Roosevelt’s workspace in front of the large window overlooking Tremont Street is covered with clamps for gluing cracked musical instruments, violins in various states of repair, and wood planers in sizes ranging from as small as a ring to as large as two hands. Some of the wood in his shop dates back hundreds of years, says Roosevelt, showing samples of cedar and spruce so dry they are light as a feather. “Wood for instrument building has to be 35 years old at least,” he says, “it has to be seasoned and dry, so it’s ready to go.” He frowns on string instruments mass-produced with wood that has been oven dried.

Roosevelt has taught string instrument and bow making to students 12 years and up, and older ones, at the BCA and the Cambridge School of Adult Education. He is looking forward to teaching more soon, as public health requirements allow.

Mr. Pires can be reached at 617 292-7788 or by email at Roosevelt.63.p@gmail.com. South End String Instrument is located at 551 Tremont Street, #201.

Theresa-India Young

Fiber Artist

FOSEL pays tribute to accomplished fiber artist, weaver, ceramicist, and educator, Theresa-India Young

Theresa-India Young was an internationally known and widely respected weaver, ceramicist, interdisciplinary arts teacher, and education consultant who worked in the Boston area from 1975 until 2008, when she passed away from cancer. Among other places, she taught studio art and museum education at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where a fiber artist scholarship is endowed in her name.

A long-time resident of the Tremont Street Piano Factory, India Young was a strong advocate of the idea that wall hangings were art, not crafts. As such, she trained students at the Museum of Fine Arts, the Peabody Museum, the Harvard University Museums, Lesley University, Wheelock College, the Cambridge Friends School, the Boston Center for the Arts, Roxbury Community College, and the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts.

Born in New York City, India Young was drawn to textiles from the age of three, when she would sort ribbons her uncle brought home from the candy factory where he worked in the Bronx. She would watch her grandmother iron the bundles she had sorted by color and weave them into throws for family members. This closeness of family and community was pivotal in her outlook on life, a belief system carried with her throughout her career. “I am an artist, woman of color, and from African diaspora,” she said.

She became known for her deeply researched teachings of techniques like backstrap, ikat, kente, European tapestry, and Navaho weaving, skills for which she traveled all over the world.

In the 1970s, at Boston’s Massachusetts Horticultural Society, with its 33,000 volumes about plant life from all over the globe, she studied natural dyes and struck up a friendship with the horticulturists. “I think they wondered, ‘who is this Black girl who comes in here to read the books?’” she told the Bay State Banner, which reviewed her exhibit of wall hangings at the Horticultural Society in the 1980s. “I kept on coming back. They saw me doing sketches. I began to get into conversations with the librarians. I found a home.” Another famous South End artist, Allen Rohan Crite, designed the invitations for her 1978 show.

At the South End Library, India Young conducted three community weaving projects, including the DNC 2004 Boston Veterans Flag; Backstrap Weaving; and Weaving Community, which was her favorite library project. During the Library’s 2019 renovation, the tapestry was damaged, but plans are underway to recreate it.

India Young was a strong supporter of community-based arts and, in 1989, co-founded the Kush Club, a teen docent program established as a collaboration between the Nubian Gallery and Egyptian Department at the MFA and the Museum of the National Center for Afro-American Artists in Roxbury.

India Young’s work has been exhibited in many locations, including Massachusetts College of Arts, the City of Boston Mayor’s Gallery, the National Center of Afro-American Arts, the Rhode Island School of Design, the Nashua Art Center, the Slater Memorial Museum, and the Warwick Museum. Her work has appeared in catalogues for juried exhibits like Atlanta Life Insurance Co., Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the National Afro-American Museum & Cultural Center Traveling Exhibit.

A new exhibit, Legacy: A Continuous Thread, Theresa-India Young & Contemporary Fiber Artists, will be at the Piano Craft Guild Gallery at 791 Tremont Street from October 1st- 25th. All proceeds will benefit the Theresa India-Young Scholarship Fund. For further information, contact:

Jacqueline L. McRath: brown.18@netzero.net

SOUTHWEST CORRIDOR PARK

A symphony for the eyes

Franco Campanello, president of the Southwest Corridor Conservancy, says “The dense plantings are a mirror of the prairies and fields across the American continent.”

If not for Franco Campanello, Southwest Corridor Park would likely still be the urban wasteland it was in the early 2000s.

Forged by the successful, two-decades struggle of many to stop an Interstate 95 Highway that would have cut through the South End, the four-mile linear park that now runs over and alongside the MBTA Orange line had been abandoned by the State and become a dangerous place. Previous efforts by volunteers to protect and restore it had failed. Half the plantings had died, weeds took over large sections, and other areas were bare and lifeless. The soil blew away in the wind.

Campanello, who founded Club Café and, with his business partner Caleb Davis, the Metropolitan Health Club, lived at 36 Claremont Park at the time and needed a project. He decided that the Southwest Corridor was a good one. Its non-profit Conservancy, founded in 2004, picked him for President. Shortly thereafter he started his new career as a restoration landscaper, “without a degree,” he says, but “no one else wanted the job.”

For starters, he signed on with Boston Cares, a non-profit that places volunteers in communities. One day a month, a corps of folks came, pulled weeds, removed bad trees and vines, spread compost and cleaned up the park. In 2008, they planted their first trees, two three-foot Hanoki Cypresses right outside the windows of Campanello’s home, now 20-foot sentinels.

Since then, more than 80 trees were added, as well as hundreds of shrubs and thousands of perennial and annual flowers. With his volunteers, Campanello put in more than 2000 hours of labor each year for the past 10 years. The dense plantings are a mirror of the prairies and fields across the American continent, he says. The trees are a selection of the great noble trees, like Sumac, Chestnut, Cypress and Tupelo, and others from the Far East, naturalized in America, such as Japanese White Pine, Maple, and Chinese Fir. “And the response of the insects and birds is a wonder,” Campanello observes.

“I have been fortunate to create beauty out of a wasteland,” he reflects. “The beauty I continue to discover as the plants grow to fullness is astounding. From tiny moss to towering Sycamore, the plants individually are a delight and, when woven together, are a symphony for the eyes. I see no reason why this Corridor Park should not be the equal to the other great parks of the city.”

Eric Knudson

An artist inspired by “conversations about identity, waste, and the environment”

FOSEL features artist Eric Knudsen whose work is informed by his experience in Provincetown and his need to create art that draws attention to larger social and political issues.

Eric Knudsen, until recently a South End resident, lived in Provincetown between 2011 and 2015, during which time he took classes at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) and at the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill. He absorbed the energy of the historic artist colony with its many galleries and practicing artists, and the magic of living by the ocean. His work is informed both by his experience in Provincetown and by his compulsion to create art that draws attention to larger social and political issues.

The designs on display here were inspired, in part, by the themed costume parties regularly held in Provincetown, including the annual Carnival parade. In the Tampini series, he attempts to leverage the attention-grabbing quality of costume to spark conversations about identity, waste, and the environment.

Often on his walks along the beach in Provincetown Knudsen would come upon trash tangled with organic debris at the high tide line and feel a sense of dismay. “Among the human-made garbage were small missile-like plastic objects that I learned were tampon applicators that had been flushed down the toilet. I was drawn to the applicators for their sleek, smooth design; they looked like part of a sea creature,” he said.

Tampini was created to be both beautiful and shocking, juxtaposing the quotidian with the disastrous. Knudsen points out that although menstruation is a natural bodily process, its management has been commodified by corporations with devastating consequences to the environment. The plastic tampon applicators, like all plastics discarded into the sea, end up in the digestive tracts of marine creatures or are degraded into small pieces that eventually enter the human food chain.

In April 2019, the Tampini artwork was featured in the Period Pop Up Art Show in Jamaica Plain sponsored by the Massachusetts chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW). The show was intended to draw attention to the state I AM bill (H.1959/ S.1274) that would guarantee equitable access to menstrual products (preferably biodegradable ones!) for people in prisons, schools, and homeless shelters. The show was also exhibited in the Massachusetts State House in September of that year.*

In addition to his interest in art, Knudsen has a background in public health and has worked in HIV prevention. In 2011, he began volunteering at a summer camp for transgender and non-binary/gender-non-conforming youth, where he since has become an associate director. Identifying as gay and queer, he lives in Jamaica Plain with his partner and their plants.

* For more information on the I AM movement, please visit http://www.massnow.org/IAM.

ACCESS: Art - An Online Group Exhibition Exploring Access and Audience

March 29—May 30, 2021

THE EXHIBITION:

ACCESS: Art is an online group exhibition curated by Amanda Contrada that explores topics of access and audience through artistic practice. The nine artists in the exhibition, all recipients of the 2020 Red Bull Arts microgrant, approach the idea of democratizing art through public installations, performance, live streaming, and digital platforms, and explore use of public space both virtual and physical.

Artists include: Allison Maria Rodriguez, Basil El Halwagy, Benny Sato Ambush, Callie Chapman, Chanel Thervil, Cindy Lu, Hector René Membreño-Canales, Julian Shapiro-Barnum, and Ngoc-Tran Vu.

THE ARTWORK:

The artists in ACCESS: Art approach the idea of democratizing art in both new and existing work. Documentation of public installations and performances, music and theatrical works presented on free digital platforms, painting and dance premiered on social media, and photography of public interventions and monuments show the breadth of tactics that artists can use to invite an audience into their practice and provide access to their art.

The photo above is a still from the 2020 Zoom performance of playwright Anthony Clarvoe's The Living, as directed by Benny Sato Ambush and captured by screenshot. It is on view as part of the digital exhibition ACCESS: Art, presented by Boston Center for the Arts across multiple platforms, including FOSEL’s Local/Focus window display on Tremont Street.

BOSTON CENTER FOR THE ARTS (BCA):

Boston Center for the Arts, founded in 1970, is recognized as a leading force in the City’s cultural community, and has supported thousands of individual artists, small organizations and performing arts companies, who add depth and dimension to the Boston arts ethos. Through innovative and critically acclaimed programming and residencies in its Mills Gallery, Plaza Theaters, and Artist Studios Building, BCA serves as an epicenter for an expanding cohort of artists working across all disciplines, and has catalyzed careers by providing fertile ground for experimentation and artistic risk-taking.

Located at 539 Tremont Street in the South End, BCA is widely known for its signature historic Cyclorama, a 19th-century domed structure that serves as a popular home for events and activities including Taste of the South End, the annual Boston Art Book Fair, and community events.

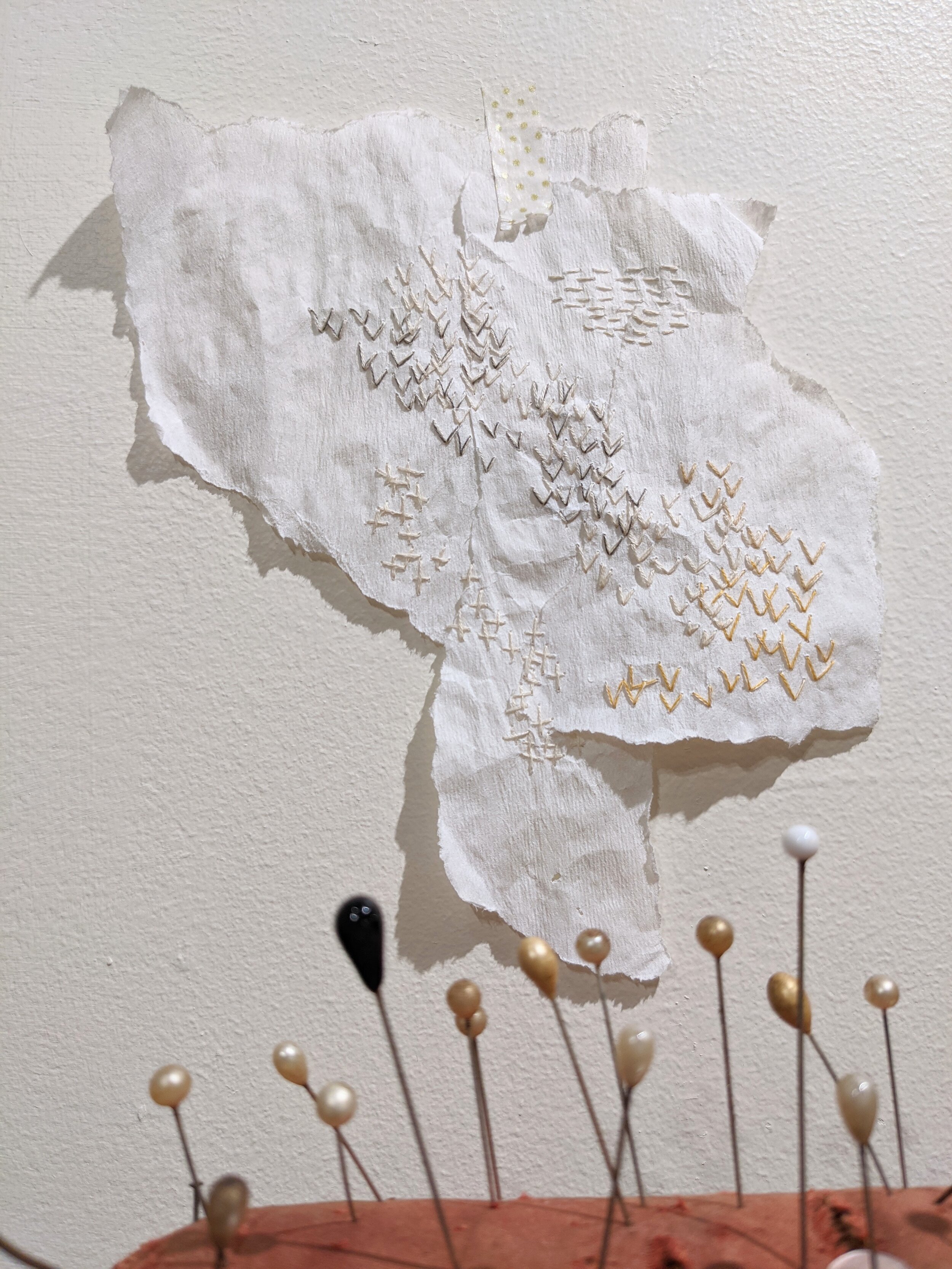

Fiber Artist Sophie Truong

Fiber artist Sophie Truong, owner of SoWa’s Thayer Street storefront studio, Stitch and Tickle

Fiber Artist Sophie Truong in front of her South End shop

Sophie Truong started out in international business but realized in her 30s that the arts were her métier, specifically, fiber arts. Born in France, Truong moved to Boston in the 1990s, where she worked for the Museum of Fine Arts for a decade.

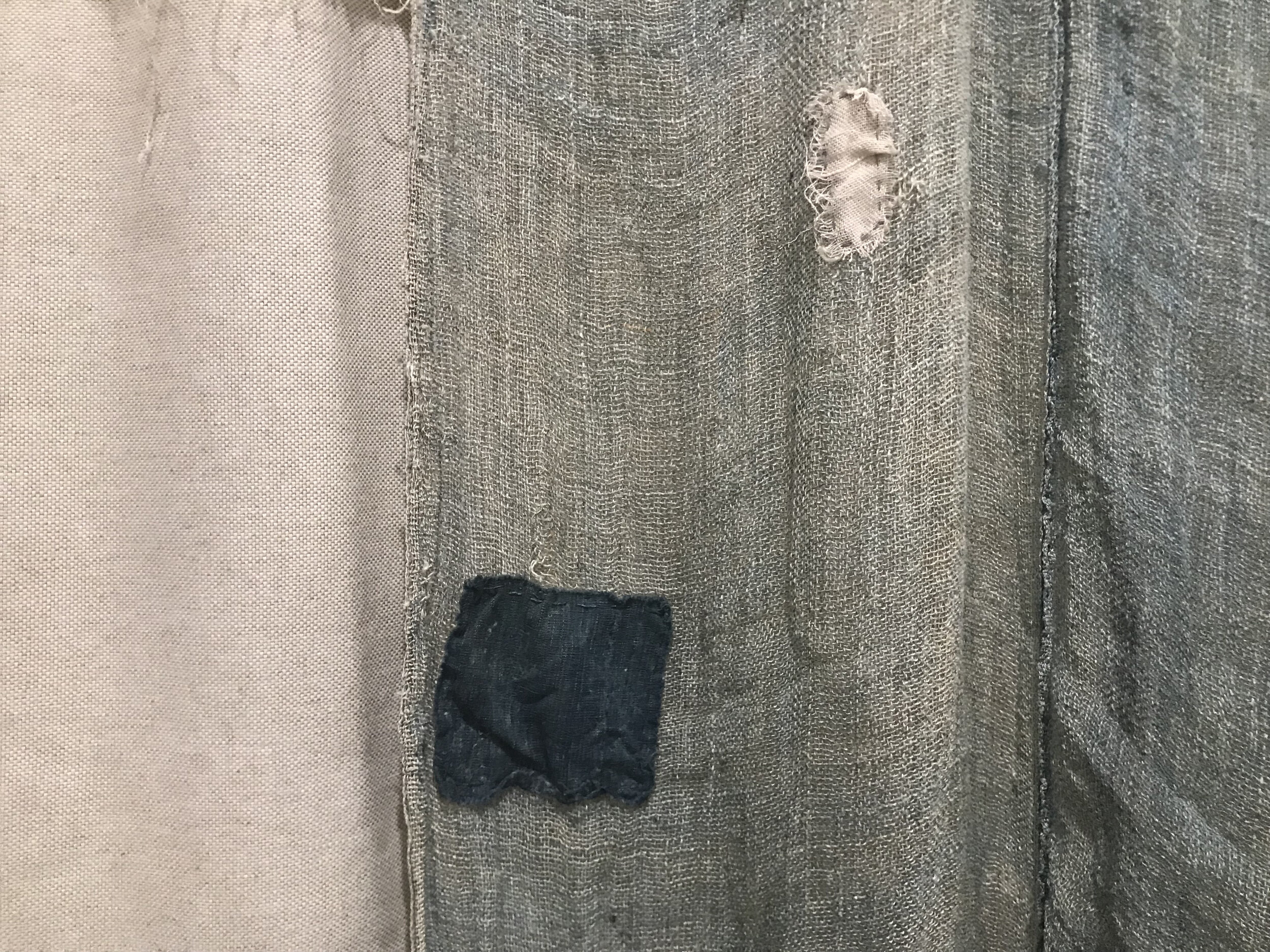

Currently the owner of the SoWa store front studio, Stitch and Tickle, Truong was named the 2020 Best Handbag Designer by Boston Magazine, but years ago became enthralled by centuries-old Japanese mended textiles, known as Boros. She embraced the visible mending technique in her work, samples of which are now on display in the Library window.

Boros, which means “rags” in Japanese, describes futon covers or garments that people from the North of Japan would make out of hemp and scraps during the Edo period (1600 – 1892). In that era, “commoners” were not allowed to wear cotton so they layered hemp for warmth, and mended it to extend its lifespan. Every scrap was saved for reuse, and furoshikis (wrapping cloths) filled with rags and shreds, were a common gift for girls getting married.

Boros fabrics are dyed with natural indigo, both for strength and to repel insects, giving it a homogeneous palette. “Their abstract composition seems to have been born out of necessity or happenstance,” instead of design, says Truong. “The repetition of repairs, the numerous and overlapping stitches and patches are what make Boros so special. Nothing was wasted and you notice the hand of the sewer in every piece.”

As with her leather handbag designs, where the leather itself dictates what the product will be, Truong looks at the Boros stitches and mending marks as drawing lines for her own artwork stitching.

Her SoWa brick-and-mortar store - Stitch and Tickle- is located at 63 Thayer Street. To contact, phone 617 792-0792 or visit stitchandtickle.com

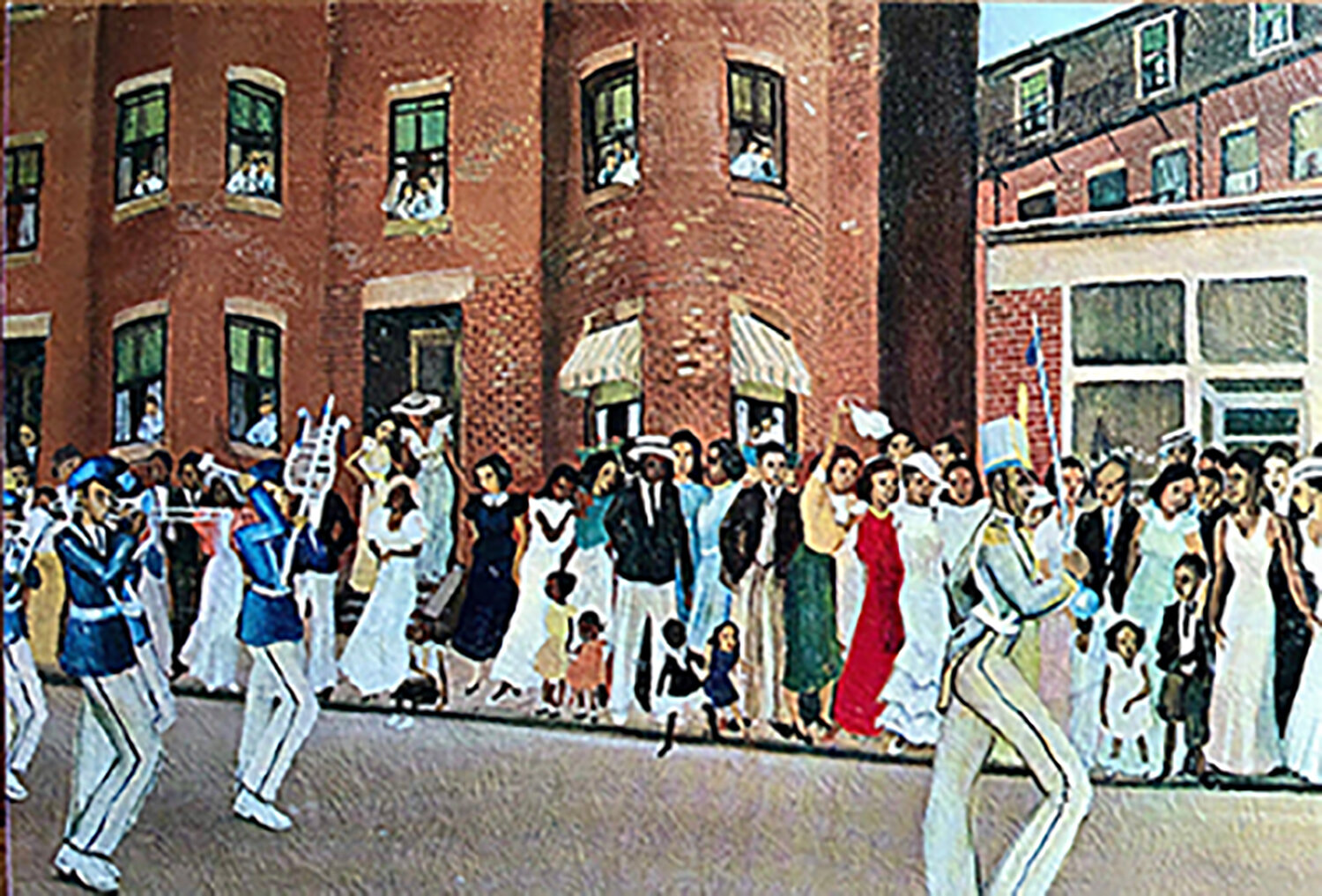

Allan Rohan Crite Park

Come see the plans for the Allan Rohan Crite Park in our Tremont Street window (through Feb. 28).

A rendering of the proposed new park at the corner of Columbus Ave. and West Canton St.

Alan Rohan Crite was a South End artist and neighborhood icon whose work has been widely exhibited and well received. Although he is best known for his religious illustrations, his early paintings depicted daily life among Boston’s African American community in the 1930s and 40s. He considered himself a biographer of the urban experience, recording what he saw, and developing a series of so-called “neighborhood paintings,” in which he presented black Bostonians “in an ordinary light, persons enjoying the usual pleasures of life with its mixtures of both sorrow and joys.”

Crite lived on Columbus Avenue in the South End and studied at Boston University, the Massachusetts School of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts School, and Harvard University. He died in 2007 at age 97.

Crite was known to neighbors throughout the South End. To this day, many residents warmly recall seeing him with his sketch pad in hand and a greeting for all. The Boston Globe referred to him as the “Granddaddy of the Boston Art Scene” and the “Dean of African-American Artists in New England.” His works are displayed in major American institutions including the Smithsonian, the Phillips Collection, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, the Boston Atheneum, and the Boston Public Library.

In 2017, a group of neighbors from the Ellis Neighborhood Association developed a plan to transform a long-neglected property at the corner of Columbus Avenue and West Canton Street, a few doors from Crite’s homestead, into a neighborhood park. Their mission was twofold: to create a welcoming green space and to memorialize Crite’s life and work.

As the Crite Park revitalization continues, residents from the South End and South Boston have joined to form the Friends of Crite Park Corp., an all-volunteer nonprofit organization working to make the new park a reality. They have already engaged a landscape architect, who, with survey input, created a design for the park that has received an overwhelmingly positive community response. They are now fundraising for construction of the park, a maintenance fund, and support for a host of planned community events that will promote the significance of Crite’s contributions to the art world and to the South End.

For information or to donate, visit ellisneighborhood.org/critepark.html and “like” Crite Park on Facebook. Email Critepark@gmail.com to receive park updates or to volunteer.